The Cold War "ended" with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the dramatic events of 1989 and the early nineties, but....well, the more things change...

And now I'm not just talking about Putin.

Essentially, the Cold War was a period of friction between two world "systems," the Communist East and the Capitalist/Democratic West. Today, we can clearly see conflict between the West and a different East--the East of Islamism/Islamic Fundamentalism. Since the events of 9/11, I'd argue that the U.S. has been involved in a different Cold War, with a different enemy. But we can see some striking similarities:

The interplay of religion. Then it was the Judeo-Christian West vs the "Godless" atheism of the Soviets. Today we are described as the infidels by Islamic fundamentalists. The occasional outbreaks of hot war: our involvement in Afghanistan and Iran today, Korea and Vietnam then. The conflicts over resources. And there are others.

I bring this up as something to keep in mind as you teach about the Cold War. It is easy--alas, I find myself saying this over and over again in this blog--to get bogged down in too much detail. The goal should not be to have students learn facts about the Truman Doctrine, the Berlin airlift, NATO, the Marshall Plan, the fall of China, the Warsaw Pact, containment, McCarthyism, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, HUAC, the U-2 incident, Cuba, Krushchev, Korea, and on and on....oh my! The goal should be

- to make connections among (some of) the items above

- to understand how our values and assumptions about the Soviet Union turned into policy

- get a sense of how the U.S. acted as one of two major powers in the world and and

- understand how the foreign policy of the United States was forever changed in ways that still have an impact today. (See cartoon at right!)

- and of course we should connect all of this to our past study of foreign policy, especially the concepts of realism and idealism. (See this previous post and this one).

To engage students in that topic, I like to show the first 20 minutes or so (I stop right before the Rosenbergs) of the documentary, Cold War Reds, 1947-1953, by CNN Perspectives. For more info on the video, including some of the criticisms of it, check out this site. I have mixed thoughts about giving students worksheets to go along with films (more on that in another post, I think), but I did choose to use one with this film. The clip is about 20 minutes, so if you devote a class period to it, you have plenty of time to stop it often so students have a chance to take notes and/or you can discuss the question as you go, or afterwards or a little of both. Find that worksheet here. Note that the last question I have on there says, "for tomorrow." That is because I the following day I like to spend on McCarthyism and connecting it to the present.

Years ago, when I taught about McCarthyism, I asked students to think of a more contemporary equivalent to accusing someone of being a communist. Often, they came up with the term, "racist." Their argument was that if a politician or other public figure was accused of saying something racist, that figure was often considered "guilty" immediately and had to "prove" that they weren't really racist, or that the comment was taken out of context. Just like those accused of being communists in the 1950s. I would argue that this is still a great example. But last spring, as I taught in a community that had a significant Muslim population, I was delighted when one of my students brought up the effect 9/11 had on Muslims in the United States. As the only student at the school who wore a headscarf, she had had personal experience with how others viewed her suspiciously and negatively simply because of the headscarf.

McCarthyism also presents the opportunity to make connections to the social conformity of the 1950s (see some of the videos and the interview in the bagtheweb lesson described in my last post), as well as racism, anti-semitism, and today's prejudice against Muslims.

For a nice "hands-on" sort of activity, check out this handout that was given to me years ago from deep in the history department's files (so I have no idea who first created it). I had students edit it directly from Google docs last year, but of course, the old-fashioned paper and pencil method works too. Following the activity, I had students write an ID, defining McCarthyism. I like to teach students early in the year how to do this, as it is a simple writing activity that can be used in class, for homework, or on tests. You can use this handout to do that.

Considering recent changes in our policy toward Cuba, it also makes sense to keep that in your Cold War curriculum. I found some really interesting resources on that last spring. Check 'em out:

- my handy google presentation that lays out the basic facts for background information

- these 3 short video clips about Castro, Krushchev and Kennedy from The Armageddon Letters are engaging for students, short (about 5 min. each) and help humanize this international crisis. I really liked them a lot. So did the students.

- I found the above videos from the Choices Program lesson on the Cuban Missile Crisis. This site has the links to the videos above, as well as suggestions for how to use them.

- I adapted this graphic organizer from the lesson above to add my own touch at the end. Check out my discussion question about the role of personality in shaping history.

- The Stanford History Education Group (SHEG) also has a good lesson on the Cuban Missile Crisis. I used the documents they suggested. Check that out here.

- Found some good stuff, too, at the New York Times Learning Blog site.

- You can put students in groups and assign each one of the following choices outlined to President Kennedy: 1. do nothing, 2. invade Cuba 3. airstrike against the missiles 4. naval blockade around Cuba 5. negotiate. And then they have to come up with reasons to support this choice. Then you can discuss what Kennedy actually did do.

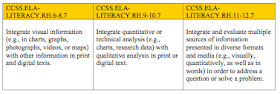

- Analyze the effect the Cuban missile crisis had on JFK and our foreign policy in general using these two speeches of Kennedy's. You can use it at the end of your lesson, or use the first at the beginning and the latter at the end. Very Common Core.

If you're looking for more Cold War materials, check out my next post.